This summer, many displaced Yazidi families returned to their places of origin in Sinjar, hoping to turn the page after ISIL’s horrible 2014-2017 siege of the city. Yet, the situation remains extremely volatile, witnessing recent Turkish airstrikes in the region. Can Cordaid’s Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) programme absorb the influx of returnees? And what is it like to deal with COVID-19 and the volatility of conflict at the same time?

From the city of Erbil, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Hala Sabah Jameel, Cordaid’s MHPSS expert and health program advisor, and Ahmad Qaradaghi, director of our implementing partner Access Aid Foundation (AAF), answered these and other questions.

Iraq’s Achilles’ Heel

“The Turkish airstrikes did not come as a surprise”, says Qaradaghi. “For decades now, armed conflicts have been part of the complex power play in these disputed areas. Unfortunately, we have become used to them.”

The areas in the North referred to by Qaradaghi – Arabised under Saddam, but populated largely by Kurds, Turkmen, Yazidi’s, and other ethnic groups – are disputed between the central Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). When they were both fighting ISIL, Kurdish troops and central Iraqi troops fiercely battled for control over these territories. The disputed territories remain Iraq’s Achilles’ Heel up to this day.

The bad luck of being strategically important

Within these territories, the Sinjar area with its mountain, its minerals, its gas and oil fields, and its proximity to Syria, has all the bad luck of being of strategic importance. The Yazidi’s, persecuted for centuries, have always managed to survive there as a people and to keep their culture alive. But the price they pay is high.

“At the moment, there at least 6 armed parties in and around Sinjar. They are continuously competing for influence and authority, with incidents and altercations every now and again,” explains Qaradaghi. These parties include police, army forces, militias backed by Iran, the Kurdish PKK, and Yazidi militias. The latter were created to organise Yazidi security, especially during and after ISIL’s genocidal attacks.

These internal power dynamics are further complicated by the military presence of foreign powers, such as the US, the EU, and Turkey.

While Shia-Sunni tensions, international geopolitics, and control over resources are at the heart of this arena, so is poverty. “A lot of young Yazidi men have joined militias and took up arms because it pays a salary. They simply have no other income or job opportunity,” Qaradaghi continues.

Dormant cells wake up

To complicate matters, instead of neutralising opponents, attacks and military operations only seem to obfuscate the situation and to deepen the conflict. Take Turkey’s massive airstrikes targeting members of the PKK and shaking Mount Sinjar in June. What happens after some Kurdish fighters are defeated? “Other armed groups fill the gaps. In this case, the airstrikes cause instability, giving dormant ISIL cells, who fled to the mountains after their defeat in 2017, a chance to come out of hiding”, answers Qaradaghi.

We had medication in stock for patients to treat their depression, but we couldn’t deliver them.

One might think COVID-19 globally tempers cross-border affairs, including warfare. It doesn’t always. Coincidentally or not, the Turkish airstrikes took place in June, when Iraq was in strict lockdown.

Providing mental care in an arena of conflict

This Sinjar arena of collective trauma and ongoing conflict is one of the areas where Cordaid and implementing partner Access Aid Foundation provide MHPSS services to both displaced people and returnees. This includes psychiatric and psychosocial services at Sinjar hospital, outpatient clinical visits, and mental health awareness sessions in different communities. This story offers an insight into some of the realities both patients and mental caregivers are forced to deal with.

Some find their homes occupied by others and have a hard time proving it was theirs.

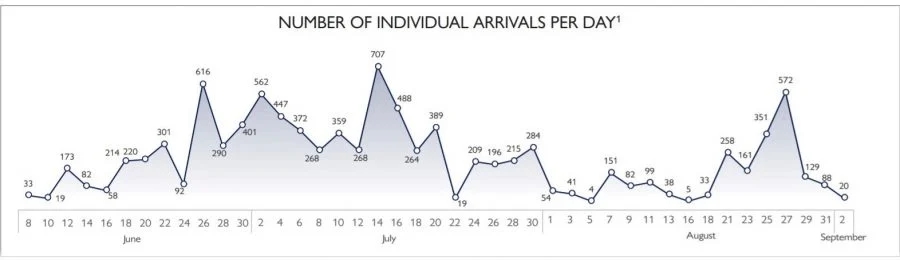

The striking thing is that between June and September, the return of displaced Yazidi’s to their places of origin in and around Sinjar increased significantly, despite lockdown measures.

Old city of Sinjar remains a site of destruction

In fact, it appears COVID-19 was one of the push factors for displaced Yazidi’s to return. Displaced families who still had members working in the area of origin, couldn’t move back and forth any longer between Sinjar and their places of temporary shelter because of the lockdowns. Urging them to return. And despite armed clashes that took place in the Sinjar mountains in those summer months, the overall security situation seems to have improved according to the IOM, with public infrastructure slowly being rehabilitated and mines being cleared. “However,” Qaradaghi comments, “rehabilitation of Sinjar is in no way comparable to for example Mosul. It’s slower and more difficult, simply because of the fact that Sinjar is part of the disputed area. That’s why large parts of the old city haven’t changed at all; they remain a site of total destruction.”

“We couldn’t even visit the hospital”

Hala Sabah Jameel, based in Erbil and the driving force behind Cordaid’s MHPSS program in Iraq, breathed a sigh of relief when severe COVID-19 restrictions were partially lifted in July. “Finally, after weeks and weeks, things started to roll again,” she says. “Before that, we couldn’t even visit Sinjar hospital. Neither could our psychiatrist, or other MHPSS staff. And due to curfews, patients we had been assisting the past year couldn’t visit the hospital either. This is why we quickly intensified our remote services, mainly by setting up hotlines and using social media. Women and children, traumatized by ISIL brutalities, by domestic violence, by loss of relatives and property, had no safe space left. They badly needed these remote services. Hotlines were a small but very important way for them to reach out.”

“We had medication in stock in Erbil for patients to treat their depression or anxiety disorders, but we couldn’t deliver them in Sinjar, a 90 minutes’ drive. This just shows how frustrating things were, for them in the first place and for us as aid workers,” Sabah Jameel continues. “Luckily, the lockdown was lifted in July. We could travel, distribute medicines. The MHPSS centre in Sinjar hospital is in business again. And, so far, we can absorb the needs of returnees. We do all we can, with the little means and staff we have. With COVID and conflict, a lot of people or on the brink of a mental breakdown, including aid and health workers. But so far, we manage.”

The increasing need for mental health care

However, with one psychiatrist from Mosul coming once a week to Sinjar hospital, seeing 20 to 30 patients on his ‘Sinjar day’, it is clear that current MHPSS services in Sinjar – one of Iraq’s humanitarian epicentres – are a drop on a hot plate. “On top of that,” says Qaradaghi, “according to UNDP, 47% of the Yazidi’s who were brutally displaced by ISIL six years ago have not yet returned. In fact, some have left for Europa and other places and will probably never return. But others will, and the need for mental health care in Sinjar will only increase in the future.”

Dr Muhazim Muhammed, the 53-year-old psychiatrist who visits Sinjar hospital every fortnight, claims he had never seen trauma on the scale he had seen in Sinjar. Knowing he comes from the embattled city of Mosul – ISIL’s stronghold for several years – gives weight to his words.

The hope and the horror of going back

Though every returning Yazidi family yearns for a life in peace and for wounds to heal, returning to Sinjar is often traumatic itself. It is the scene of home but also of horror. No one is free from the need of care and assistance, both from near ones and from professionals. On top of that, there are crippling issues of joblessness and house ownership. Some find their homes occupied by others and have a hard time proving it was theirs. Sometimes, if they can’t, they have to flee again, often to the mountain, joining the thousands who have already been surviving there for years. Some don’t find their homes, because it was destroyed. Some are assigned a home in another part of the city because their old neighbourhood is still mined. Sometimes Sunni Arabs – a minority in Sinjar – want to return to their house but are driven back by Yazidi’s who have occupied their properties. Anything remotely associated with ISIL is banned.

Administration: a battle within a battle

“As citizens in this part of the world, and as aid workers, we have been dealing with the consequences of conflict for a long time,” says Qaradaghi. “For ages, actually. We have learned to deal with that. What disables us most in our humanitarian mission, is the administrative battle. There are so many powers and authorities we have to ask for approval with every step we take. As the conflict evolves, their spheres of control shift and switch. Meaning that realities and security on the ground can change from week to week, even from day to day. This day we can pass a checkpoint, the next we can’t. Every hours’ drive, means passing several checkpoints, controlled by different parties, asking for stamps of approval and paperwork many days in advance. Time and again, in every place you come, we have to prove we are neutral and in no way connected to any of the many parties involved in the conflict. At the same time, you have to work with these parties, as you are passing their areas of control. Keeping this balance is extremely time- and energy-consuming.”

Time and again, in every place you come, you have to prove you are neutral.

Together with Iraq’s health authorities, Cordaid and AAF have a long-term mission in helping to heal trauma’s in this nook of Iraq’s mountainous North. Painfully enough, staffing hospitals and mobile health teams, providing medicines, setting up hotlines, and helping survivors of unspeakable injustices and horrors on their way to some kind of recovery, is the easiest part.

This story is written by Frank van Lierde, Corporate Journalist at Cordaid; first published on cordaid.org

Read more about Cordaid’s health care program.