In 2021, the government failed to deliver on its promises to hold to account those responsible for the arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings of protesters, activists, journalists, and others openly critical of political and armed groups in the country.

Iraq’s criminal justice system was still marred by the widespread use of torture, including in order to extract confessions. Despite serious due process violations in trials, authorities carried out at least 19 judicial executions of defendants sentenced to death.

No ISIS defendants have been convicted of international crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide. In March Iraq’s parliament passed the Law on Yazidi Female Survivors, which recognized crimes committed by ISIS against women and girls from the Yezidi, Turkman, Christian, and Shabaks minorities as genocide and crimes against humanity, but little progress has been made towards applying the law.

In a brazen attack on November 7, unnamed armed actors tried but failed to assassinate the prime minister in his home using three armed drones.

Accountability for Abuses against Critics

During protests that began in October 2019 and continued into late 2020, clashes with security forces, including the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF or hashad) nominally under the control of the prime minister, left at least 560 protesters and security forces dead in Baghdad and Iraq’s southern cities. In May 2020, when Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi took office, he formed a committee to investigate the killings of protesters. It had yet to announce any findings as of September 2021.

In July 2020, the government announced it would compensate the families of those killed during the protests. As of September 2021, the six families of activists killed whom Human Rights Watch contacted had not received any compensation. In February 2021, the government announced the arrest of members of a “death squad” that had allegedly been responsible for killing at least three activists in the southern city of Basra. Baghdad authorities announced in July that they had arrested three low-level security forces officers linked to abuses against protesters, and one man allegedly responsible for the 2020 killing of political analyst Hisham Al-Hashimi.

A United Nations Assistance Mission to Iraq (UNAMI) report published in May found that not one of several arrests related to targeted killings appeared to have moved beyond the investigative phase. As of late September, it appeared that none of the arrests had led to any charges being brought.

Torture, Fair Trial Violations, and the Death Penalty

UNAMI released a report in August based on interviews with more than 200 detainees, over half of whom shared credible allegations of torture. The report found that the authorities acquiesce in and tolerate the use of torture to extract confessions, a finding consistent with Human Rights Watch reporting on the systemic use of torture in Iraq.

Criminal trials of defendants charged under Iraq’s overbroad terrorism law, most often for alleged membership in the Islamic State (ISIS), were generally rushed and did not involve victim participation. Convictions were based primarily on confessions including those apparently extracted through torture. Authorities systematically violated the due process rights of suspects, such as guarantees under Iraqi law that detainees see a judge within 24 hours, have access to a lawyer throughout interrogations, and that their families are notified and be able to communicate with them.

Based on the criminal age of responsibility in the penal code, authorities can prosecute child suspects as young as 9 on terrorism charges in Baghdad-controlled areas and 11 in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. This violates international standards, which recognize children recruited by armed groups primarily as victims who should be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society, and call for a minimum age of criminal responsibility of 14 years.

According to a Ministry of Justice statement in September, authorities were detaining close to 50,000 people for suspected terrorism links, over half of them sentenced to death. Informed sources told Human Rights Watch that at least 19 executions had been carried out as of September. Those imprisoned for ISIS affiliation reportedly include hundreds of foreign women and children , though children are not sentenced to death.

Many defendants were detained because their names appeared on wanted lists of questionable accuracy or because they were family members of listed suspects.

In the Kurdistan Region, the Kurdistan Regional government (KRG) has maintained a de facto moratorium on the death penalty since 2008, banning it “except in very few cases which were considered essential,” according to a KRG spokesperson.

ISIS Crimes Against the Yezidi Community

Despite ISIS’s systematic rape, sexual slavery, and forced marriage of Yezidi women and girls, prosecutors neglected to charge ISIS suspects with rape—which carries a sentence of up to 15 years—even in cases where defendants admitted to subjecting Yezidis to sexual slavery. Instead, Iraqi judges routinely prosecuted ISIS suspects solely on the overbroad charge of ISIS affiliation. No ISIS defendants have been convicted of international crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide, despite the apparent genocide by ISIS against the Yezidis.

On March 1, 2021, Iraq’s parliament passed the Law on Yazidi Female Survivors, which recognized crimes committed by ISIS including kidnapping, sexual enslavement, forced marriage, pregnancy, and abortion against women and girls from the Yezidi, Turkman, Christian, and Shabaks minorities as genocide and crimes against humanity. The law provides for compensation for survivors, as well as measures for their rehabilitation and reintegration into society and the prevention of such crimes in the future. In September 2021, the parliament passed the necessary regulations to implement the law but by November, little progress had been made towards applying the law.

Collective Punishment

In March 2020, the government endorsed a National Plan to Address Displacement in Iraq calling for a thoughtful and sustainable approach to assisting Iraq’s protracted displaced population. However, the government closed 16 camps between October 2020 and January 2021, leaving at least 34,801 displaced people without assurances that they could return home safely, get other safe shelter, or have access to affordable services. Many residents were female-headed households displaced by fighting between ISIS and the Iraqi military from 2014 to 2017, and many of these families were being labeled ISIS-affiliated.

Only three camps remain open in Baghdad-controlled territory, two in Nineveh and another in Anbar.

In July, the Iraqi army unlawfully evicted 91 families from a village in Salah al-Din to one of the Nineveh camps in an apparent family feud involving a government minister.

In 2021, security forces continued to deny security clearances, required to obtain identity cards and other essential civil documentation, to thousands of Iraqi families the authorities perceived to have ISIS affiliation, usually based on accusations that an immediate family member of theirs had joined the group. This denied them freedom of movement, their rights to education and work, and access to social benefits and birth and death certificates needed to inherit property or remarry.

Authorities continued to prevent thousands of children without civil documentation from enrolling in state schools, including state schools inside camps for displaced people.

The government allowed some families to obtain security clearances if they filed a criminal complaint disavowing any relative suspected of having joined ISIS, after which the court issues them a document to present to security forces enabling them to obtain their security clearances.

At least 30,000 Iraqis who fled Iraq between 2014 and 2017, including some who followed ISIS as it retreated from Iraqi territory, were held in and around al-Hol camp in northeast Syria. In May, the Iraqi government repatriated 95 Iraqi families from al-Hol and in September at least another 20 families. Authorities have prevented some of them from leaving the camp freely, retaining cell phones, or returning home.

The KRG continued to prevent thousands of Arabs from returning home to villages in the Rabia subdistrict and Hamdaniya district, areas where KRG forces had pushed ISIS out and taken territorial control in 2014 but allowed local Kurdish villagers to return to those same areas.

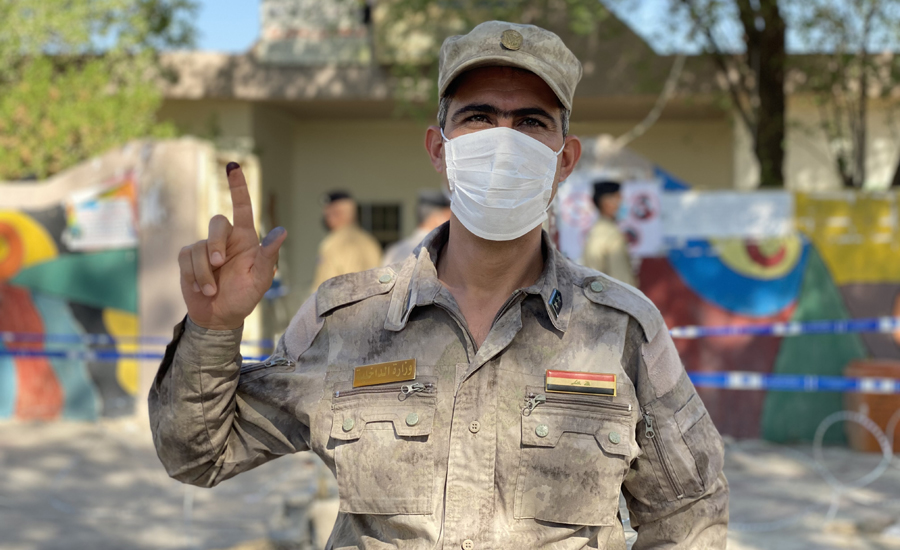

Elections

On October 10, Iraqis voted for a new parliament with a voter turnout of 36 percent. Prominent Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr’s movement secured the largest number of seats in peaceful elections.

People With Disabilities

Iraq failed to secure political rights, in particular the right to vote, for Iraqis with disabilities. People with disabilities are often effectively denied their right to vote due to discriminatory legislation that strips the right to vote or run for office for people considered not “fully competent” under the law, inaccessible polling places, and legislative and political obstacles, like requirements for a certain level of education that many people with disabilities are unable to attain. In 2019, the UN’s Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities said that Iraq, plagued by decades of violence and war, including the battles against ISIS from 2014-2017, has one of the world’s largest populations of people with disabilities.

KRG Prosecution of Critics

In 2021, the Erbil Criminal Court sentenced three journalists and two activists to six years in prison, based on proceedings marred by serious fair trial violations as well as high-level political interference. The court rejected the defendants’ claims of torture and ill-treatment, citing a lack of evidence. Another journalist was sentenced to one year for misuse of his cell phone and defamation charges in June and September. Another four activists and journalists arrested in 2020 were awaiting charge as of October 2021.

Women’s Rights, Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, Morality Laws

While Iraq’s penal code criminalizes physical assault, Article 41(1) allows a husband to “punish” his wife and parents to discipline their children “within limits prescribed by law or custom.” UNICEF surveys have found more than 80 percent of children are subjected to violent discipline. The penal code also provides for mitigated sentences for violent acts, including murder, for “honorable motives,” and catching one’s wife or female relative in the act of adultery or sex outside of marriage.

Such discriminatory laws expose women to violence. Cases of domestic violence were reported throughout 2021, including killings of women and girls by their husbands or families.

Parliamentary efforts to pass a draft law against domestic violence has stalled since 2019. The 2019 version seen by Human Rights Watch included provisions for services for domestic violence survivors, restraining orders, penalties for their breach, and establishment of a cross-ministerial committee to combat domestic violence. The bill had several gaps and provisions that would undermine its effectiveness, such as prioritizing reconciliation over protection and justice for victims.

In 2021, Iraqi security forces arbitrarily arrested lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people based solely on their gender non-conforming appearance, and subjected them to ill-treatment including torture, forced anal exams, severe beatings, and sexual violence, in police custody. Security forces also physically, verbally and sexually harassed people they perceived as LGBT at checkpoints. Human Rights Watch documented cases of digital surveillance by armed groups against LGBT people on social media and same-sex dating applications. The government has failed to hold accountable members of armed groups who have abducted, raped, tortured, and killed LGBT Iraqis with impunity.

Article 394 of Iraq’s penal code makes it illegal to engage in extra-marital sex, a violation of the right to privacy that disproportionately harms LGBT people as well as women, as pregnancy can be deemed evidence of a violation. Women reporting rape can also find themselves subject to prosecution under this law. Iraq’s criminal code does not explicitly prohibit same-sex sexual relations, but Article 401 of the penal code holds that any person who commits an “immodest act” in public can be imprisoned for up to six months.

Key International Actors

On January 3, 2020, a US drone strike killed Lt. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, at Baghdad airport. Two days later, Iraqi parliamentarians passed a non-binding resolution to expel US-led coalition troops from the country. In mid-2021, President Biden said that by December 31, US troops would end their combat mission in Iraq but would continue to provide training and advice to Iraqi forces.

Turkish airstrikes continued in 2021, targeting the Iranian Kurdish Party for Free Life of Kurdistan (PJAK) and Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) members based in northern Iraq, in some cases killing civilians. Human Rights Watch was unaware of any investigations by the Turkish military into possible unlawful attacks it had carried out in northern Iraq or compensation of victims.

In 2017, the UN Security Council created an investigative team, UNITAD, to document serious crimes committed by ISIS in Iraq. Given the deeply flawed Iraqi criminal proceedings against ISIS suspects and ongoing fair trial concerns in the country, it remained unclear to what extent the team has supported the Iraqi judiciary in building case files in line with international standards.

* The link for above "World Report 2022" by HRW is: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/iraq