An estimated 1.8 million people remain displaced across camps and informal housing arrangements across Iraq despite the end of fighting.

According to a follow-up by Balkis Wille, senior Iraq researcher and director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa Division, various obstacles are hindering the return of displaced families, including security instability and fear of revenge attacks from neighbors.

Since mid-2014, when the Islamic State (IS) group swept through large swathes of territories across several Iraqi provinces, more than 5.8 million people fled their homes.

According to the Human Rights watch report, out of the 1.8 million still in displacement, some 450,000 live across 109 camps , while another 1.2 million in private or informal housing arrangements.

Forced Returns

Many families were forced to return home despite that their homes were devastated.

In Tal Abu Jarad, a village in Salahaddin province which was controlled by ISIS for several years, “some 60 families had returned to rubble because local leaders ordered authorities in the areas where the families had been living to evict them to force them back.”

The report indicates that they were forced to return only “to attract aid to the area” by humanitarian organizations.

Imprisoned in Camps

The HRW report refers to dramatic shift in the feelings of the people in the camps. In 2016, they were “happy to be back under Iraqi government control and receiving services, three years on, with no sign that they will be allowed to return home, these families now seethe with anger and resentment toward the authorities”, according to the report.

IDPs felt frustrated, arguing that authorities have done little to help displaced reintegrate into Iraqi society.

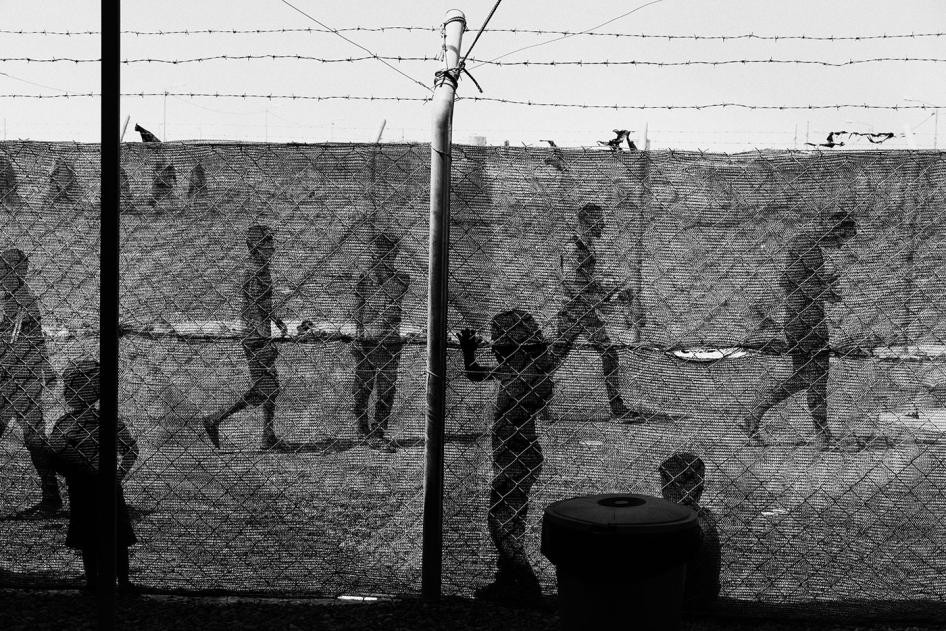

A camp south of Mosul housing families displaced by fighting between ISIS and Iraqi forces, Photo: Moises Saman/Magnum

Areas of No Return

According to figures released by humanitarian workers in Iraq in 2019 as many as “242 distinct areas in Iraq have been identified where not a single family has been able to return even though the fighting ended, in some cases as long as five years ago.”

Factors that set back the return of these families were represented by landmines and other forms of explosives, booby-trapping homes which IS left behind and have yet to been cleared.

Meanwhile, “in 94 of the areas, the de facto ban on returns is a form of punishment against those the security forces perceive as having been sympathetic to ISIS, or as having a relative who was sympathetic to the group,” the report indicated.

The number of people from families with perceived ISIS affiliation who could not return home because of objections by federal or local authorities or communities are estimated to be 250,000.

Prevented Return

Balkis Wille, director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa Division recalls that an Iraqi soldier she met in December 2018 at Kilo 18 IDP camp in Anbar province told her that “only three families were allowed to go home after they had fulfilled the requirements of finding a community leader and 10 witnesses to testify they never had sympathy for IS”, while the rest were being moved on to other camps.

“One elderly woman who wanted to go home was from an area in Anbar province where the majority tribe was claiming that members of her tribe had joined ISIS and demanded huge payments to allow families to return.”

Dozens of families told similar stories.

Detentions in Camps

The HRW report reveals that some of the camps have become detention centers, such as the Ishaqi camp in Salahaddin which Belkis Wille describes as “infamous” because there is no international or local organization present to manage the camp.

According to HRW inquiries, residents of the camp suffer from horrific conditions, including lack of fuel, and the chronic diseases.

According to statements by camp residents, fighters of Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) “rounded up all 52 men in the camp between the ages of 17 and 57 and took them away, along with a few younger boys.”

Denial of Security Clearance

Security clearance is one of the tools of collective punishment against families with perceived ISIS affiliation. The security clearance is needed to replace any missing civil documentation.

“To obtain this clearance, families need to approach the designated intelligence force in their area where officers will run their names through a database of people flagged as “wanted” for their suspected links to ISIS. If their relative is on one of those lists, officers will deny them clearance,” as observed by HRW.

Based on estimates by aid groups, in early 2019 at least 156,000 displaced people are missing at least some of their essential civil documentation.

Children from families living in a tent in a camp south of Mosul, March 2017 Photo: HRW

Overcoming Restrictions on Movement and Returns

In some areas a practical solution has emerged for obtaining security clearance so relatives of IS suspects can return home.

In the fall of 2016, Anbar community leaders got the judiciary to agree that if a wife, father, sister, or other relative of an ISIS member who is missing— perhaps dead, perhaps disappeared—makes a criminal complaint against that relative over his IS membership in front of a judge, the judge will issue a document that green-lights their security clearance”, according to the HRW report.

The director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa Division describes the practice is “inappropriate”. “No one should have to open a criminal complaint against their husband to secure basic rights”, she said.

Segregation and Fear in Sinjar

Balqis Wali in her report says that in late 2018 she visited four Arab villages in Shingal (Sinjar), where families had returned willingly in June 2018.

“From 2014 to 2017, these families had remained and lived under IS. At the same time their Ezidi neighbors suffered from sexual slavery and killings by IS. After the area was retaken from IS, the Arabs fled and the Ezidis began to return.”

Sunni Arab familie who returned to their villages claimed that they were threatened by some of the Ezidis who formed armed groups under the patronage of the local PMF.

“As of early 2019, about 80,000 Ezidis had returned to their original homeland in Sinjar, while another roughly 300,000 were still living in camps in northern Iraq, waiting to go home,” the report indicates.

Internally displaced people at a checkpoint south of Mosul, August 2016 Photo: UNHCR

Rehabilitation

In 2019, Iraqi authorities began considering a proposal to construct large-scale detention sites that they are calling “residential compounds” for families with perceived ISIS affiliation “to target them with deradicalization programming.”

The families housed in these compounds would not be allowed to leave while they live there.

The government tried to establish such a rehabilitation camp in 2017 but abandoned the effort.

Where from here?

Concluding her report, Balkis Wille expresses fear that “by marginalizing these families, punishing them for the real or perceived acts of family members, and by depriving them of the opportunity to reintegrate into their communities, the country is pushing them back into the arms of recruiters like IS.”

She mentions Rawan, whose son was detained because her husband fought with IS as an example of this fear. “This generation will grow up to become barbaric… the government needs to put them back in school and issue them their identity papers so this generation can forget about IS.”