Women farmers participate in Iraq’s agricultural sector at nearly twice as many men, a pattern also reflected in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), according to the 2021 Labor Force Survey. Yet this high level of involvement places women at the center of the sector’s hardships. In the absence of meaningful government subsidy and amid worsening economic conditions, farmers are increasingly compelled to rely on pesticides to protect their crops. Due to high costs and limited alternatives, farmers turn to banned or smuggled pesticides as they are more affordable than those officially approved under Iraqi law, despite the serious health risks they pose. Female farmers, in particular, bear the heaviest health and economic consequences.

This investigation documents the extensive use of pesticides banned by the Ministry of Agriculture MoA and exposes how traders, importers, and shop owners bypass regulations. By exploiting legal loopholes, corruption among certain officials, and the desperation of farmers, these actors continue to flood markets with unsafe chemicals: pesticides and insecticides.

Survey results from the provinces of Dohuk, Nineveh, and Basra reveal that 91.5% of farmers rely on imported pesticides, while 28.5% admit to using products that are restricted or banned.

For decades, Zainab, family breadwinner, personally handled pesticide spraying. She used to buy supplies from Baghdad and occasionally received subsidized ones from the Directorate of Agriculture.

“I spray the pesticides with my hands,” she recalls. “We even use chemicals and chicken manure on the plants. I carry the container on my back and spray it.”

Without masks or gloves, Zainab sprayed trees to eliminate scorpions and venomous snakes. She still remembers how the chemical fumes caused coughing, lingered on her clothes and mixed with the taste of the rice she prepared afterward, while remnants of old ammunition near the orchards contaminated irrigation water.

Her forced displacement from the farm, under constant threat of death, marked the beginning of another struggle.

Two weeks after fleeing south, Zainab experienced chest pain and was diagnosed with breast cancer. She underwent surgeries in 2015 and 2019. Tough back to her hometown, now she endures chemotherapy and costly bone injections instead of looking after her orchard. Although doctors have not definitively linked her illness to pesticides, Zainab is certain she was exposed to grave danger.

"The pesticide, the war, it could be either, but we were never protected."

Zainab’s experience reflects a broader reality. Nineveh, one of Iraq’s most agriculturally productive provinces, records the highest pesticide consumption nationwide.

Dr. Balqis Suhaim Al-Ali, pollution expert, explains that pesticides can cause cancer and birth defects over time due to residue accumulation in the environment and their transfer through the food chain.

Data from the Cancer Statistics Center in 2023 underscore the severity of the situation: women make up 58% of cancer cases in Nineveh, with breast cancer the most common diagnosis, particularly among women aged 50 to 54.

A similar story unfolded in Basra

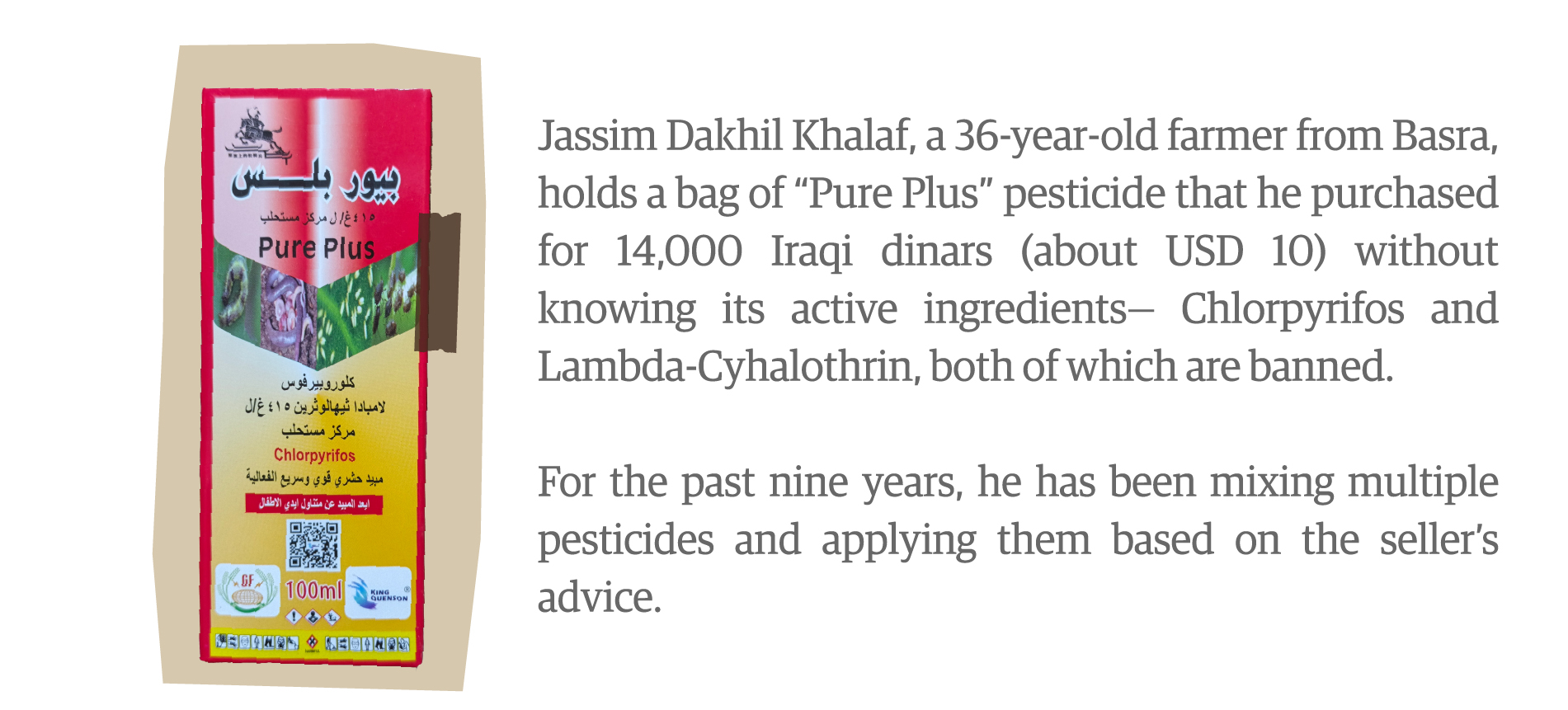

In the tomato fields of Muwailihat, southwest of Basra, Umm Majid, a 57-year-old farmer, spent years mixing and spraying pesticides with her bare hands, unaware of the dangers of (Malathion and Imidacloprid). “I was only fourteen or fifteen when I began,” she says tiredly. “My brother and I planted tomatoes, and I was the one who sprayed the crops.”

Umm Majid spent her youth working hard on the farm, mixing pesticides herself and preparing them for use, filling barrels with litres of pesticides, and spraying crops without a mask or protective gloves.

“I used to cover my nose with a plastic bag just so I could breathe, and then we sat down for lunch as if everything were normal.”

Moving slowly, her joints aching, Umm Majid makes her way toward the bed before pausing to explain further: “When the seeds turn green, we add Khayis (Malathion). Once the plant grows a bit, we spray it with Super (Dimethoate) and finally Quaitia (Imidacloprid). We repeat it every month, and when the plant blossoms, we spray it with Dursban (Chlorpyrifos).”

The merchant was the one who explained how to use it. “We purchase it from the seller, and he tells us how to apply it,” she says, adding that after every spraying, they experience breathing difficulties and painful skin irritation.

Years later, she was diagnosed with uterine (womb) cancer.

Like Zainab, Umm Majid was also forced to stop farming due to illness. With a tone of regret, she explains, “We used to depend solely on the seller’s instructions, and most people were illiterate.”

In a similar story, Umm Wissam, 55, lives in Khor Al-Zubair with the grief of losing her first child shortly after birth. ‘We don't have hereditary diseases, we don't have anything.’ She believes years of pesticide exposure contributed to her loss, a concern supported by scientific studies linking pesticide exposure before pregnancy and during the first trimester to stillbirth.

Like Zainab and Umm Majid, Umm Wissam handled pesticides with little knowledge or protection. “We would buy whatever was available, pour it into barrels, mix it with our hands, and spray,” she recalls.

“Sometimes we forget to wash our hands before eating.” Today, serious illness has forced her out of farming. She suffers from severe respiratory problems, chronic lung inflammation, arterial blockages, and has undergone four cardiac catheterization procedures between 2014 and 2023.

She says no one ever warned her or offered guidance. “I never saw an agricultural engineer or landowner help us,” she says. “If the government had supported farmers properly, things would not have reached this point.”

Pesticides: The Poison Seeping into Farmers’ Bodies

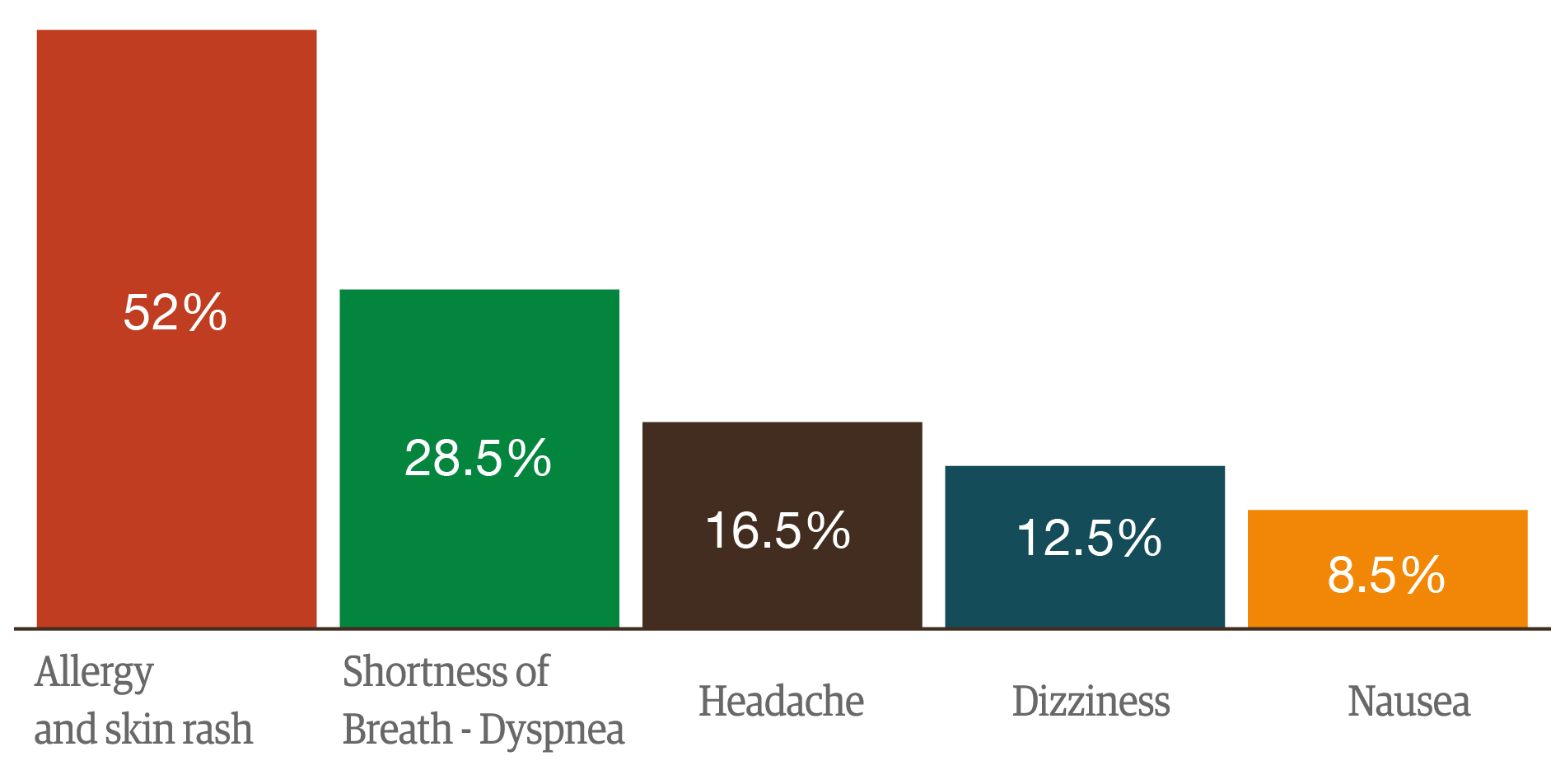

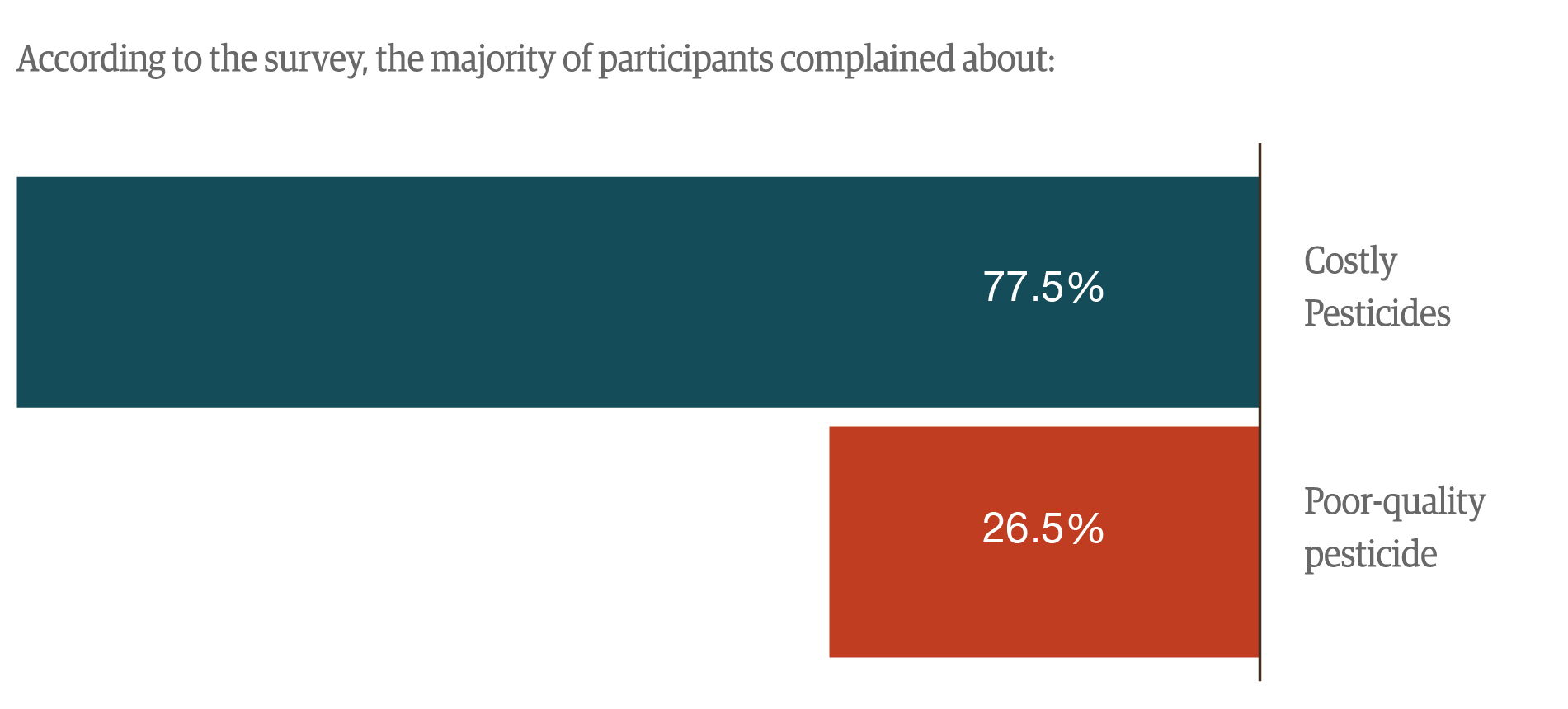

The exposure to large quantities of pesticides can cause acute poisoning and long-term health effects, including cancer and reproductive disorders, the World Health Organization WHO warns. A survey, conducted by the investigative team, of 200 farmers across Dohuk, Nineveh, and Basra provinces found that skin allergies, rashes, and breathing difficulties are among the most common symptoms following pesticide exposure.

While the spokesperson for the Ministry of Health, Saif Al-Badr, denies that the ministry has recorded any cases related to pesticides, it is noteworthy that the majority of respondents to the survey did not consult a doctor or do not consult one, which may explain the absence of accurate official statistics on the extent and impact of highly toxic pesticides on citizens' health. It should be noted that these symptoms also affect their families, as 14% of survey participants reported that a family member had contracted an illness that could be linked to pesticides.

Masoud Hussein Musa, a professor of plant protection at the University of Duhok, confirms that pesticide exposure is directly linked to these symptoms, especially among children and pregnant women.

“Strong pesticides can cause reduced IQ levels or birth defects,” he warns.

Dr. Ammar Hazem Hamed, Zoonotic Diseases specialist at the Nineveh Health Directorate, adds that repeated exposure leads to the accumulation of carcinogenic substances, increasing the risk of miscarriages and congenital abnormalities.

Scientific research further reinforces these concerns. Studies show that women whose husbands use pesticides and insecticides like Chlorpyrifos at home face a significantly higher risk of breast cancer. Other research links Malathion and Diazinon to damage to the female reproductive system, associating Malathion with uterine and ovarian cancers and long-term fertility problems.

Poor Support and Limited Care

The experiences of Umm Zainab, Umm Majid, and Umm Wissam illustrate a persistent failure of institutional support over the past two decades, particularly in providing training on safe pesticide use and proper crop protection.

In this context, Hanan Sadiq, an agricultural engineer and owner of a nursery in Basra, draws attention to the need for the Ministry of Agriculture to support women farmers in particular, explaining that women are responsible for their families and providing for their needs.

“Of course, if a woman farmer falls ill, the family will suffer both health-wise and financially.”

Khawla Salim, a social and environmental activist with the Zhingazan (environmentalist) organization in Dohuk, adds that the lack of support discourages women with agricultural degrees from entering the sector.

“Most women currently working in agriculture come from poor backgrounds and rely on outdated methods,” she says. “Environmental conditions have changed, and we urgently need scientific knowledge and expertise.”

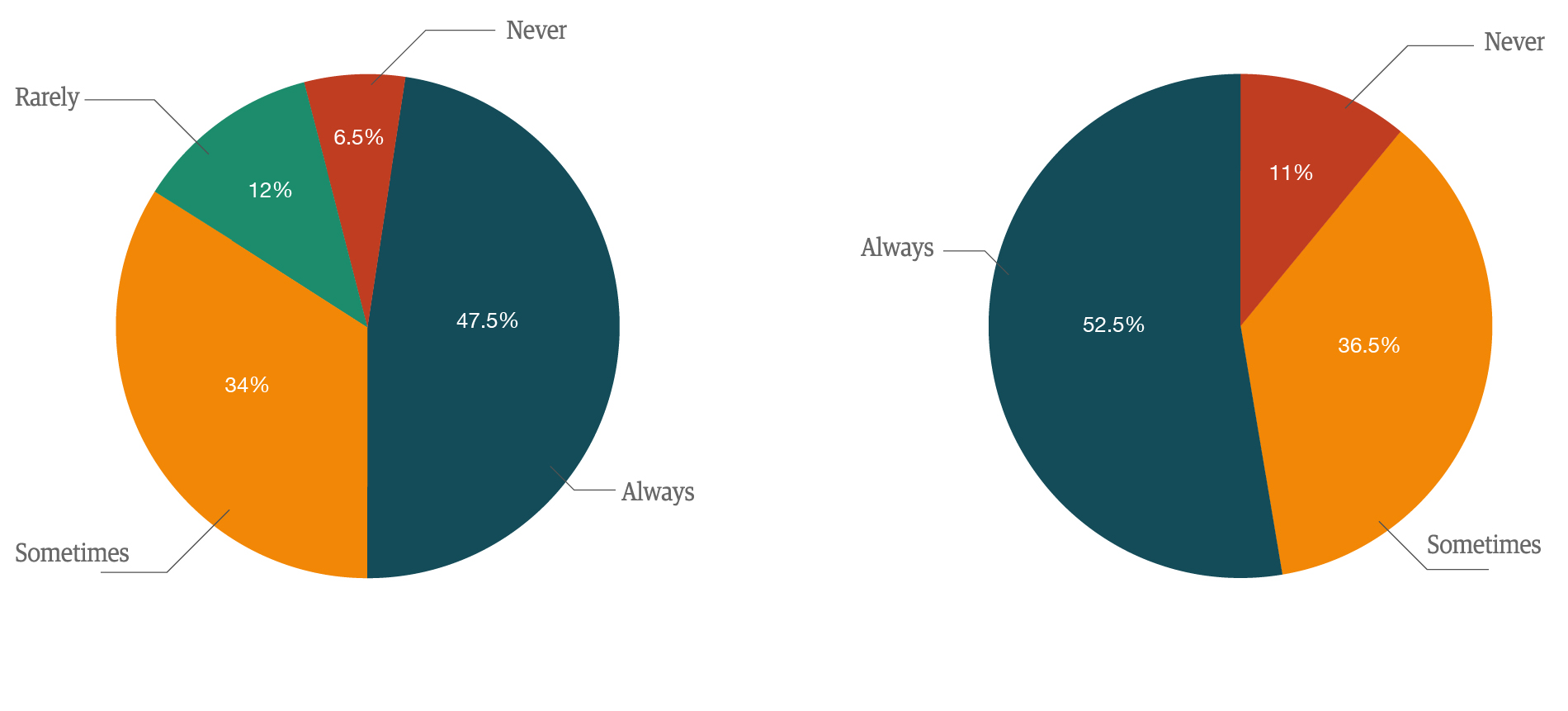

Despite evolving circumstances, awareness of pesticide risks—whether banned, restricted, or counterfeit—remains dangerously low. Survey data show that 43% of farmers do not know the names or registration status of the pesticides they use. More than half fail to read safety instructions, nearly half do not use protective equipment, and 66% have never received any formal training on safe pesticide handling.

Why Farmers Turn to Banned Pesticides?

Ahmed Ali, 24, lives beside his farm in Tal Afar, where he has been cultivating grapes, figs, fruit trees, and wheat. For the past eight years, like many farmers, he has not received formal training and is unaware of the official lists of banned pesticides. In the absence of guidance from agricultural engineers, he depends almost entirely on advice from pesticide shop owners. At times, he even prepares chemical mixtures himself at home—a practice that has left him suffering from chronic eczema for years, despite wearing gloves.

“My hands start itching and feeling hot. I go to the doctor, it gets better for a few days, but then the problem comes back… I end up using ointment every day.”

Although his doctor advised him to stop using pesticides, Ahmed says he has no alternative. The pain worsens at night, yet he continues spraying his crops. “This is our livelihood,” he explains. “I can’t give it up.” Determined to protect his harvest and increase productivity, Ahmed uses various pesticides especially insecticides, without considering their long-term risks.

The impact extends beyond him. His family now suffers from allergies caused by pesticide fumes drifting from the farm to their home.

Harsh economic conditions and the absence of meaningful support from government bodies or civil organizations continue to push farmers like Ahmed toward unsafe choices.

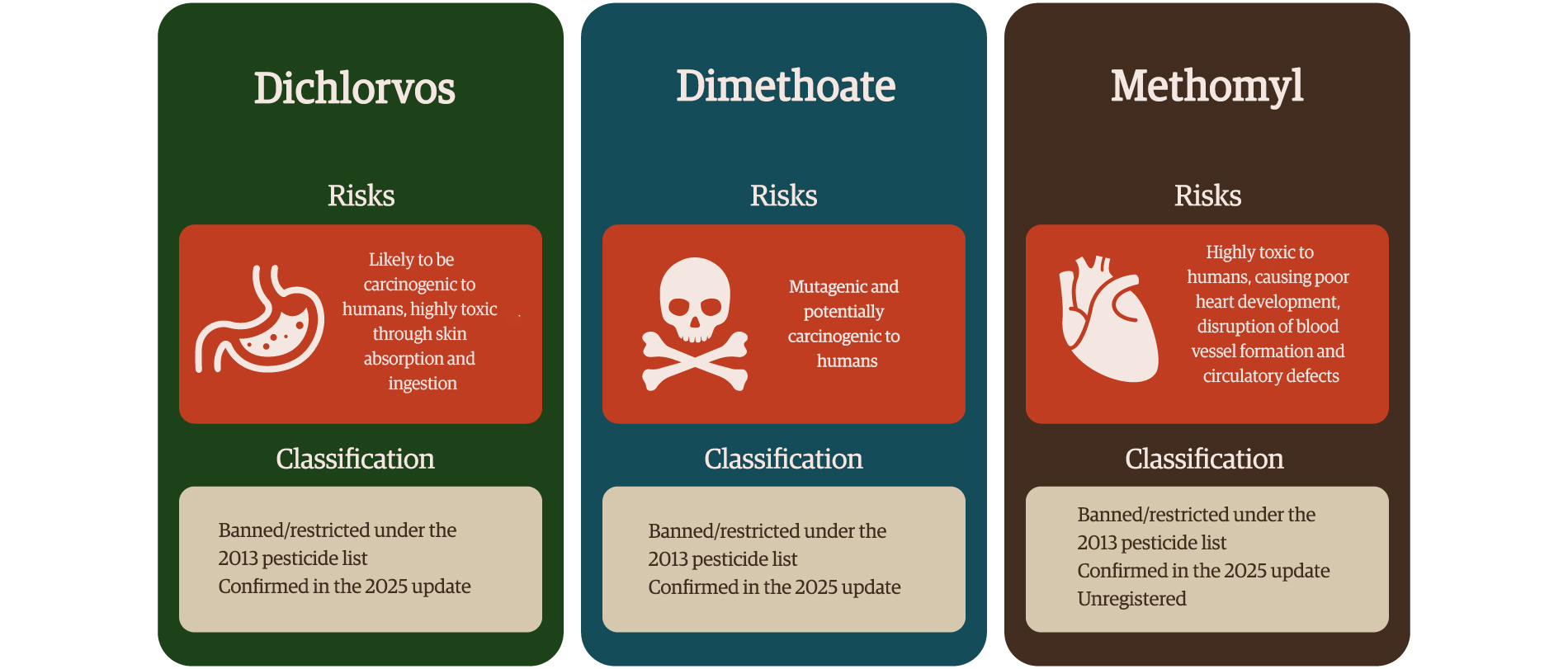

Mohammed Taha Abdul-Jabbar, an agricultural engineer at the Basra Agriculture Directorate, warns against the continued use of the Vydate insecticide, its active ingredient, Oxamyl, is internationally banned due to its link to infertility.

“It is cheap and imported from China,” he explains, noting that the pesticide has been listed as restricted since 2013 and is fully banned under the updated 2025 regulations.

Similarly, professor Musa points out that some hazardous pesticides, such as Paraquat, are still available in limited quantities because farmers lack affordable and effective alternatives.

Survey data confirm this reality: 91.5% of respondents use imported pesticides, and 28.5% rely on products that are restricted or banned.

A Field Visit to Basra

“I buy pesticides from the agricultural supply store; I don’t read the label.”

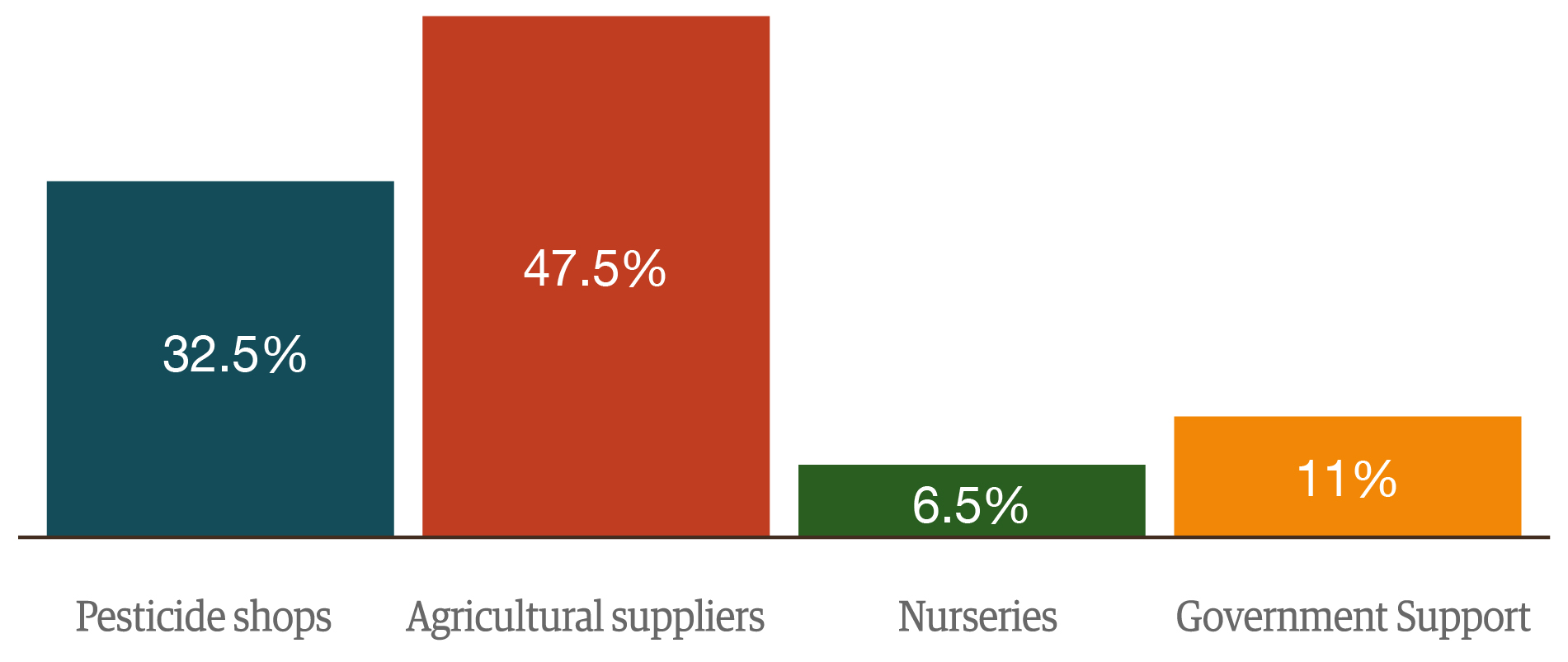

During a field visit to Basra last September, the investigative team observed banned and restricted pesticides being openly sold at a plant nursery. Initially, the nursery owner denied their availability. However, he later admitted that some of the products had recently been banned and acknowledged selling them despite legal prohibitions. He claimed the pesticides were supplied by a “powerful and influential” major trader.

The team documented four pesticides purchased from the nursery that were either banned, restricted, or expired, with some expiration dates extending only until June 2025, including:

The National Committee for the Registration and Approval of Pesticides: Regulatory Laws

Under the regulations of the National Committee for the Registration and Approval of Pesticides, companies must submit comprehensive scientific and technical documentation to register pesticides. This includes details on the pesticide’s name, target pest, origin, toxicity studies, chemical composition, packaging, and safety measures. Applications are reviewed by the committee, followed by laboratory testing and field evaluations conducted by specialized researchers.

According to the spokesperson for the Ministry of Health, all registered pesticides are subject to the conditions and instructions of the World Health Organisation, the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the Cancer Research Centre, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the European Union.

The law also requires clear labeling on containers, including active ingredients, application methods, warnings, expiration dates, toxicity classifications, and country of origin.

Traders exploiting legal loopholes

Despite these strict rules, banned and unregistered pesticides continue to flood Iraqi markets. Abdul-Jabbar attributes this to loopholes in the registration system. He explains that while Iraq follows European Union standards, some importers rush to bring pesticides into the country without registration to avoid potential financial losses in case those substances are later banned in Europe.

“Some traders and companies import the products illegally before completing the registration process,” he says.

companies that market registered pesticides pay fees to the government and conduct trials to prove their effectiveness, and these costs are added to the price of the product. Professor Musa adds. “Unlicensed pesticides, by contrast, avoid these costs and are sold much more cheaply.”

The affordability of unregistered or smuggled pesticides partly explains why farmers use them, despite the harm they cause to their health—particularly in the absence of welfare or economic support from relevant ministries and organisations, as reflected in farmers’ testimonies and questionnaire responses.

This reality, according to Raad Kreidi Al-Abadi, head of the local union of agricultural cooperative societies in Basra, has effectively turned farmers into victims of commercial companies. He warns that farmers face serious risks due to the widespread use of agricultural pesticides, many of which are not subject to proper quality control.

Hanan Sadiq, an agricultural engineer and nursery owner in Basra, agrees, stressing the urgent need to make safe pesticides accessible and to confront corruption within the sector.

“There’s significant corruption in this area, making it essential to have proper monitoring and integrity committees.”

Similarly, Abdul Hamid Fath Al-Youssef, head of the Farmers’ Associations Union in Nineveh, highlights unethical practices used by some commercial offices to market counterfeit or expired pesticides. “They remove the original label and replace it to avoid losses when pesticides sit in storage,” he explains. Farmers, he adds, are unable to distinguish genuine products from fake ones. “They buy them believing they are safe, and this ends up harming both their crops and their health.”

Al-Youssef’s remarks align with earlier observations by agricultural engineer Abdul-Jabbar regarding widespread counterfeiting. He compares the abundance of brand names—many imported from China—to “walking down an endless road of names,” making it nearly impossible for farmers to identify authentic products.

Fatima (a pseudonym), an employee at the Basra Agriculture Department, explains that pesticide effectiveness depends on the active ingredient, which may remain effective for weeks, months, or even years. However, she notes that identical active ingredients are often marketed under different brand names by different companies, further confusing farmers.

Sana Sakhr, supervisor of the Prevention Section in the Safwan Agriculture Division of the Basra Agriculture Directorate, points out that the main problem lies in the fact that pesticide office and agency owners are taking advantage of the current open borders and freedom of import. She says: ‘In the past, we supplied them with pesticides, but after 2003, the owners of the offices began buying pesticides themselves because of their low prices in the markets. However, these pesticides do not enter through the Ministry of Agriculture but through private imports.”

Pesticide imports to Iraq have tripled in value between 2011 and 2021. The 2024 import report shows Iraq’s heavy dependence on China, Iran, and Jordan for agricultural inputs, particularly pesticides.

While Sakhr confirms that pesticides imported by the Ministry of Agriculture meet safety standards, she estimates that 25–30% of those imported by private agencies are unsafe. She points to Methomyl—a pesticide commonly used in tomato farming—as an example, noting that it sells for as little as 3,500 Iraqi dinars IQD (about USD2) per package and is readily available through office owners and traders in Baghdad’s Sinak district.

Smuggling Through Border Crossings

This led the investigation team to the Sinak area of Baghdad, where some traders and officials at pesticide import companies provided information that cannot be published but which corroborates what other sources, who agreed to speak to the investigation team on condition of anonymity, said about how banned and unregistered pesticides reach the market.

According to an anonymous source, quantities of banned pesticides enter Dohuk through smuggling.

“Some farmers buy new or unregistered pesticides before they are officially approved,” the source added. “Additional shipments sometimes arrive from Mosul through illegal routes, accounting for roughly 5–10% of the total.”

Luay Muhammad Abdu, head of the Plant Protection Division at the Sumel Agriculture Directorate, disputed this assessment, saying conditions have improved. “There is greater awareness now and stricter enforcement,” he said, noting monthly inspections of agricultural offices to verify registration certificates and expiration dates. “Any violations result in sales bans.”

However, a pesticide shop owner in Dohuk, on the condition of anonymity, acknowledged that “small quantities of unregistered pesticides still enter through Baghdad. These shipments are transported illegally in small trucks, sometimes hidden inside ordinary cartons or routed through areas such as the Mosul Dam.”

The investigation team also interviewed a southern customs source, Qasim Saad (a pseudonym), who detailed how banned pesticides are facilitated through border crossings. He explained that while some shipments are officially rejected, intervention by powerful figures can reverse decisions within hours. “The law of force overrides customs regulations,” he said. “There is pressure stronger than all of us.”

He explained how importers circumvent the law to bring in prohibited items, such as packing them in commercially licensed containers labelled with the names of safe items, ‘the containers are all replaced when they arrive.’ He adds that the switching and packaging operations do not take place inside Iraq, but rather that the shipments arrive ready and packaged with fake commercial labels. ‘They switch the containers and change the names, but the substance is the same.’ The names, commercial logos and scientific names are replaced. ‘They change them in Iran, where they are loaded and arrive complete and ready.”

Saad’s account aligns with statements made by Al-Abadi, who noted that “some materials enter Iraq labeled as products from one country while actually being manufactured elsewhere.

Their labels are changed outside Iraq and marketed locally under different names,” Al-Abadi said, “placing these products beyond the reach of effective quality control.”

Saad goes on to describe how customs clearance offices inside ports are often controlled by influential figures who manage checkpoints and work shifts. To facilitate the entry of shipments, bribes ranging from $3,000 to $20,000 are paid. Shipment sizes vary widely: mixed consignments may reach up to 10 tons, while single-type shipments typically start at 24 tons and can range between 10 and 80 tons, depending on the cargo and container type. As a result, there is no fixed shipment weight.

“The customs broker is the one who pays the bribe to the employee who releases the vehicle,” Saad explains. Some shipments are deliberately delayed in official records until arrangements are made, after which they are reclassified as “safe” goods. Even when companies are caught violating regulations, Saad says they are able to resume operations by simply changing their names. “Companies that are fined more than once are always told to change their names.”

Although some improvements have begun in monitoring technologies, Saad notes that inspection and detection equipment is often nonfunctional or used only symbolically. “They say the equipment is broken, yet fees are still collected for incoming vehicles,” he says, adding that no real inspections take place. He concludes that these highly toxic pesticides—banned under the Stockholm Convention—enter Iraq “in plain sight, but with tacit agreement.”

Weak oversight and significant challenges

Najlaa Al-Waeli, Director General of the Technical Department at the Ministry of Environment, acknowledges major obstacles to effective monitoring, particularly at border entry points.

“Some entry points are not controlled, or there is insufficient awareness of the substances entering the country,” she explains, noting the detection of large quantities of unregistered and unapproved pesticides flooding local markets.

She adds that some traders deliberately exploit the system, importing dangerous, low-quality, or untested pesticides and selling them at cheap prices, despite clear laws and procedures.

On the other hand, Al-Waeli explains the relevant committee has ordered the withdrawal and confiscation of unauthorized pesticides but granted importers and shop owners a grace period until the end of 2025 to submit registration applications, allowing them to avoid financial losses and to halt the circulation of products not approved by the Ministry of Agriculture.

Al-Waeli also points out that the Ministry of Agriculture lacks enforcement authority, such as an environmental police force to coordinate with border crossings. This gap has led to coordination efforts between ministries, particularly the Ministry of Agriculture and the Border Ports Authority, to develop mechanisms for controlling pesticide entry.

An employee at the General Authority of Customs cited additional challenges, including weak infrastructure, limited laboratories, outdated detection equipment, and a shortage of sniffer dogs. He also highlighted the importance of coordination with Kurdistan region authorities to improve border control. While customs authorities are responsible for enforcing import laws—and while agricultural pesticides are classified as restricted goods requiring security approvals—overlapping jurisdictions among enforcement agencies often create confusion. “Everyone says it’s my authority,’” he remarked.

The investigation team repeatedly sought comment from the General Authority for Border Crossings but was told to contact either the Ministry of Agriculture or the Ministry of Environment. As for the Ministry of Agriculture, despite repeated attempts by the investigation team and obtaining preliminary approval to conduct an interview with the Directorate of Plant Protection, no response had been received at the time of writing.

Proposed Solutions to Iraq’s Pesticide Crisis

Experts agree that safeguarding agriculture and protecting the health of farmers and consumers requires urgent action. They stress the importance of field-level awareness campaigns, helping farmers identify safer pesticides, and integrating health specialists into agricultural offices.

Shams Abdul Rahman, a researcher in plant protection at the College of Agriculture, explains that effective pesticide regulation depends on stronger monitoring and improved agricultural extension services. This includes updating import and distribution laws, enforcing stricter penalties for smuggling, adopting digital databases, and training border personnel.

Fatima from the Basra Agriculture Department emphasizes the need to educate farmers about active ingredients, especially since identical chemicals are often sold under different brand names. Ongoing training and guidance, she says, are essential. Sanaa Sakhr of the Basra Agriculture Directorate adds that strict adherence to technical guidelines and safety intervals during spraying is critical to protecting consumers.

Al-Waeli notes that efforts are underway “to upgrade environmental laboratories for more accurate pesticide monitoring.” She also points to a national plan promoting biological alternatives to chemical pesticides and encouraging climate-smart farming.

“Pesticides are not always the solution,” she says. “There are safer, more natural, and environmentally friendly alternatives.” She further stresses the importance of involving civil society, the public, and even traders in developing a comprehensive pesticide management strategy.

Experts and farmers alike emphasize the need to enable farmers to purchase high-quality pesticides instead of resorting to cheaper, dangerous options, while also protecting local agricultural production. Environmental activist Khawla Salim notes that many female farmers struggle to sell their produce. “You see elderly women selling vegetables for 500 or 1,000 dinars, with no support,” she says, adding that imports undercut local products.

“The goods we bring in from abroad cost less than what is produced locally.”

She echoes the need for marketing support for domestic produce, pointing out that imported goods are often sold more cheaply than local crops. Salim also stresses the importance of encouraging women to enter agriculture by providing proper equipment and scientific expertise, particularly in Dohuk, where female participation in farming is nearly nonexistent.

Altogether, these testimonies expose a dual market: one regulated by strict laws and costly standards, and another dominated by unregistered, dangerous products circulating through smuggling, corruption, and weak accountability. As a result, the pesticide issue in Iraq remains an open file on a silent but ongoing health and environmental disaster.